A History of Argentina's Magnificent, Broken-down Necropolis

In Buenos Aires there is an immense oasis sprawling over gentle slopes, and beneath the earth: a cemetery in the quiet neighborhood of Chacarita, nestled next to barrios Colegiales, Palermo and Villa Crespo. Graveyards are one of my favorite places to explore and photograph – they often have lovely old trees – this one, Chacarita Cemetery, has an origin more grim than ordinary, and is one of the most fascinating places I have ever been.

Spread over 95-hectares, Cementerio de la Chacarita is almost twenty times bigger than Cementerio de la Recoleta, the famed resting place of Eva Perón and many other wealthy families. Almost half of barrio Chacarita's territory is occupied by it.

17th century Jesuits lived on the land where barrio Chacarita is today, but they were expelled in 1767 by the Spanish Royal Crown. The name Chacarita comes from the Spanish word chacra for small farms like the ones belonging to the Jesuits.

It was clear once we looked at a map that Chacarita's cemetery is massive. It is not just a dominating landmark of the barrio, but also a significant feature of the city. There are other extensive green spaces, like Los Bosques de Palermo, and numerous other parks spread throughout the city for the enjoyment of some 3 million residents, but this cemetery is a distinctly quiet place.

I didn’t really grasp the magnitude until putting eyes on it after trekking across Palermo before an upcoming move brought us to the adjacent neighborhood. Zoë and I were living in Palermo, the hippest hood in town, on Guatemala y Armenia (not far from Tufic). We had thoroughly enjoyed that arrangement, but were moving one neighborhood away to Villa Crespo to seek a different experience, and perhaps more peace.

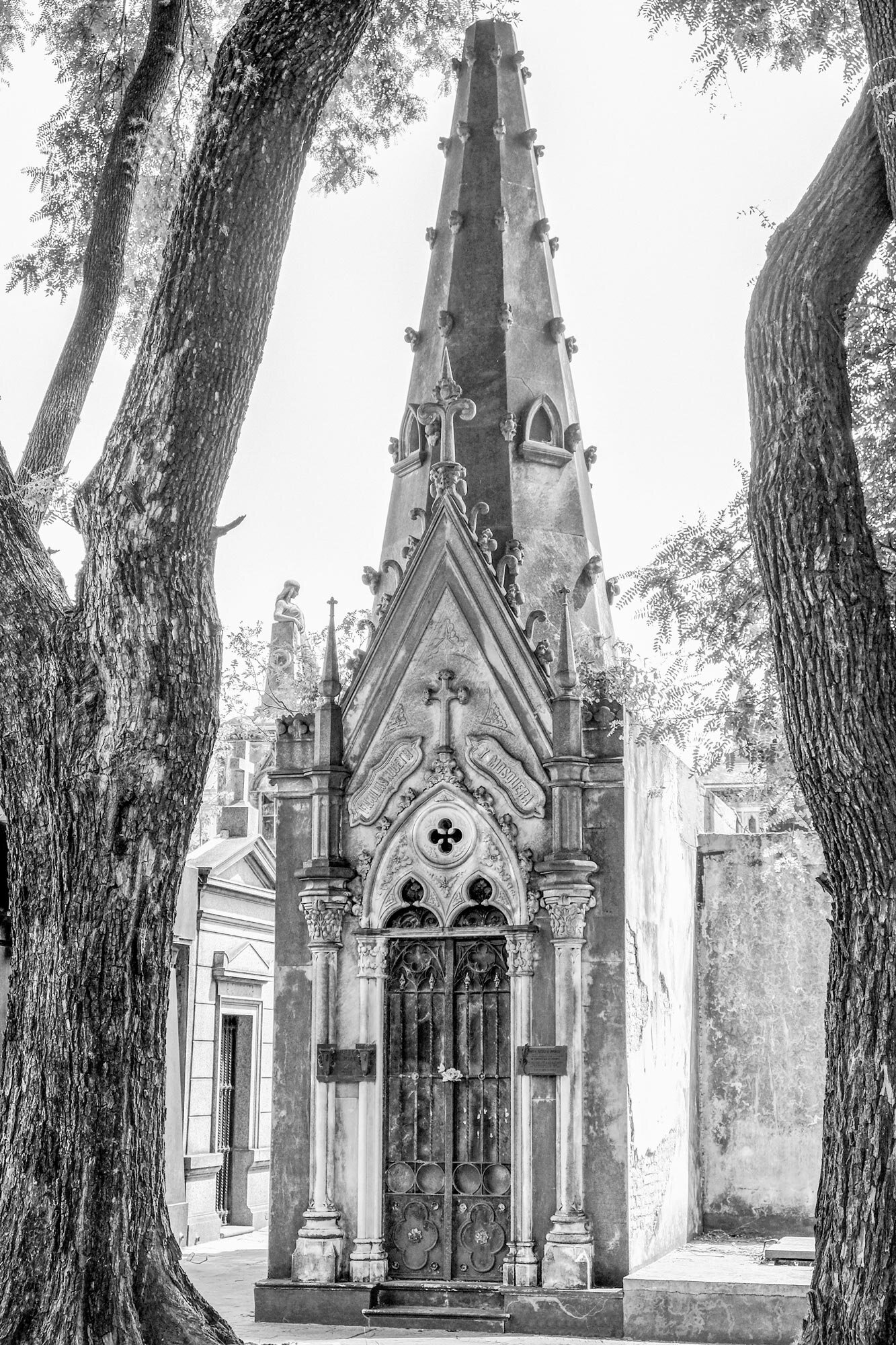

With what must be 30 foot high walls around much of the property, Cementerio de la Chacarita is like a fortress. I wrote about this first encounter briefly in an earlier essay, and the stupefied feeling the sunset introduction gave me when I glimpsed golden streets of mausoleums through a gateway.

I returned to explore within shortly after we moved apartments. I strolled up and down the somber streets of tombs, and quickly observed that some were cared for and others were falling apart. One mausoleum's marble surfaces would be so pristine that I could see my reflection, whereas the one next door may have broken panes of glass and trash accumulating inside.

I wove through, trying not to miss any details, and eventually emerged at a new segment of the cemetery. It didn't look like much: an expanse of grass with several large concrete awnings spread across. It was also a hot day, and I wasn't overly interested in spending much time in the sun without water, but I went out to get a closer look.

I remember approaching a railing and looking over, down into the earth, and seeing a verdant courtyard several levels below ground. It was surrounded by layers of catacombs. I realized, then, that those great awnings were entryways down into the underground galleries of Argentina's past lives.

I returned again and again to wander the catacombs. I love the vibrancy of Buenos Aires, but silence is what truly nourishes me, and down there I found a new experience with silence that was enhanced all the more by the scenes I saw. I spent hours underground trying to be lost, trying to find every last corner and seek photographs that could describe the feeling. I was struck by the contrasts – shades of lost civilizations and brute futurism, vastness and intimacy.

Outbreak

1871 was a devastating year for Buenos Aires and neighboring cities, and Cementerio de la Chacarita is intrinsically linked to it. An outbreak of yellow fever, the mosquito-borne virus, struck the barrios near the port, lowlands, and floodplain areas where mosquitoes could easily proliferate, and soon it was everywhere. Mosquitoes are difficult to avoid even when one is aware of the threat they can pose, but at the time it was not even understood that they were the carrier.

The Episode of the Yellow Fever, circa 1871, by Juan Manuel Blanes is a haunting rendition of the pain brought to Buenos Aires, but also a depiction of illness befalling a specific household. One wonders how many scenes like this the People's Commission had to see. José Roque Pérez is depicted in the center with with his hands clasped.

The epidemic wreaked havoc in the city, with hundreds of deaths every day during its height. Also known as "black vomit," the illness upended daily life as businesses closed, residents fled, and thieves ransacked.

The dead were so many that wagons couldn't transfer them quickly enough, furthermore, the existing cemetery space that would accept victims of the fever became full. Coffins soon accumulated at the gates as the disease spread by leaps and bounds.

The city needed to increase its burial grounds, and Chacarita was chosen as the location for a new cemetery. Cementerio de la Chacarita was inaugurated on April 14th, 1871. The first to be buried was a bricklayer named Manuel Rodriguez.

The Western Railway quickly extended a line that would transport the accumulating dead. The train that performed this twice-daily task was named La Porteña, but became known as the "train of death."

The People's Commission was soon formed to handle the ravages of the epidemic across the city. The leader, José Roque Pérez, a prestigious lawyer shown in the painting to the left, succumbed to yellow fever along with many others who did not flee.

Over 13,000 people of the city's some 180,000 residents died in just several months, before the cold arrived and killed off mosquitoes. Normal life resumed in time, but this quote from Guillermo Hudson's "Ralph Herne" indicates that the city was haunted by the catastrophe for years after:

"...But the years of peace and prosperity did not delete the memory of that terrible period when during three long months the shadow of the Angel of Death extended over the city of the nice name, when the daily harvest of victims were thrown together — old and young, rich and poor, virtuous and villains — to mix their bones in a communal grave, when each day the echo of footsteps interrupted the silence less often, when like the past the streets became desolate and grassy."

Cementerio de la Chacarita has since become a place of worship and remembrance. Everyone is welcome in Chacarita, from the less-fortunate to the famed. The soil there is for intellectuals, artists, boxers and ordinary people. Cementerio de la Recoleta, which turned away victims of the epidemic, has always been more aristocratic and exclusive.

While Chacarita receives more residents than Recoleta, it has far fewer visitors. During my time there I never saw any other rovers like myself, just visiting relatives, caretakers, and a funeral gathering. I found it comforting that it's still a very personal place for Argentines. I felt privileged to explore the grounds and tried to maintain a respectfully low profile.

It was inaugurated as the "Cemetery of the West" in 1886, but its popular name stuck, and it was officially renamed in 1949.

Over the years its mausoleums became equally as splendid as Recoleta's, with an abundance of styles and design. Its grandeur endures, but has become worn down in many places. Though some of its aging is serious, I never thought of it as anything but beautiful.

Recently the union workers formally expressed their concern about the aging. There is a degree of abandonment, and water damage, which has resulted in the crumbling of masonry and deterioration of ceilings.

The underground galleries are the most worrying in regard to potential structural issues. In many ways they are lovingly tended to, but there are damaged ceilings and broken floors all around. As well, many of the elevators are out of order, lights are missing, and there are pigeons nesting all over. Saplings have sprouted in odd places and some of the gardens are in need of pruning and attention.

I do not know when the catacombs were built, but based upon some of the building methods and mechanical features I would guess it was in the 1960s. Thinking back on how many nameplates I passed, I could've looked for dates to try to ascertain a general period of time, but the number was overwhelming.

Around the world there has been a shift, over the last few decades, toward cremation instead of burial. It seems this and the correlating decline of visitations have contributed to delinquency in payments for the niches of the galleries.

The declining number of burials and visitations signifies a cultural change in how people remember their loved ones. This could be confirmed by the florists that are found around the outside wall. Those who come to leave flowers in the tombs and in the niches are often elderly people who still retain the customs of other times.

If Cementerio de la Chacarita is to remain a safe and beautiful place, it may need monetary help in a big way before much longer. For now, in its massive underground breezeways there is a pull between the polished, sterile spaces that are both immaculate and neglected, and the lush groves that are at the same time cultivated and wild.

I'll conclude with with this description I wrote after my first day in the catacombs:

"Daylight filters in from the surface with the chatter of swirling green parrots, all else quiet. There is an allure to staying in the cool air of this geometric cavern, wandering what seems like an unknowable layout, but much of the sense of calm I feel may be reliant upon this subterranean library of the dead's frequent connection to the sky and wind."

Empress Of - "How Do You Do It " (Yours Truly session)

Kindness - "Cyan"

Nightmares on Wax - "Be, I Do"

An Electrifying Concept that will Save the World

It won’t be long until we power everything in the world with wind, water and sun. This is strategic electrification, and its game-changing disruptions will help us stop carbon pollution and increase energy efficiency. The sooner we adopt this strategy of progress, the sooner we see the benefits.

The Fore Street Garage solar canopy in Portland, ME has 7 SMA Sunny Tripower inverters flying high. Inverters convert DC from the solar panels to AC for usage in homes and offices.

There’s hundreds of years’ worth of coal underground for us to burn, but it’s going to stay there. We no longer need it to make electricity.

Historically, grid operators have created electricity with problematic resources like coal, natural gas, or nuclear energy – but due to the emergence of renewables and electrification, the nature of the grid has begun to change.

Electricity is becoming cleaner at an impressive rate, and the time is right to electrify everything. Whether it comes from residential solar systems or our growing asset of utility-scale renewable energy systems, clean power will flow into an increasingly electrified world of devices.

Green Pastures

The beauty of strategic electrification is that as electricity becomes cleaner, so will everything we do with it. As utilities invest more into renewable energy infrastructure, electricity will steadily use less fossil fuel per kilowatt-hour of energy produced. If we power our grid with 100% renewable energy, we can nearly eliminate greenhouse gas emissions altogether by electrifying everything under the sun.

To bolster the penetration of renewables on our electric grid, and to see the biggest benefit of electrification, we need to electrify space heating, water heating, and, especially, transportation. With today’s heat pumps, heat pump water heaters, and next-generation electric cars, we already have the solutions.

The Flexibility to Give

Not only will these devices be cleaner than their predecessors, they will also be more flexible, smarter. The modern grid will become smarter, too, and increased flexibility in generation, interconnection, storage and demand response around the grid will meet the challenges of a more electrified world.

The Brunswick Landing microgrid in Maine will demonstrate the grid of the future, accomplished by embracing new technologies and attracting renewable energy businesses who can use the microgrid to develop their businesses and beta test new technology.

The variability of certain renewable resources like wind, solar or tidal energy presents a challenge to generating power smoothly at all hours, but properly mixing those different resources from around the grid will create the flexibility needed to respond to changes in demand and supply.

Though it is also possible to import electricity across network borders to help stabilize the grid, flexible interconnection with the growing amount of residential solar electricity in our own network is the better way to meet that need. Decentralizing our grid in this way allows for power to be consumed where it is produced, lowering rates for everybody.

Battery storage is often heralded as the best solution to variable power production, and it will indeed play a part, but it is a higher priority to integrate and balance available renewable energy resources. That said, batteries are an obvious way to help, especially as their costs drop and capacities grow.

Flexi-Watts

Load flexibility, or demand response, will have a critical part of balancing a renewable energy grid, as it is the most cost effective method. Demand response programs existed in the past to balance supply and demand by prompting large, industrial customers to lower their usage at certain times of day during periods of high power prices or when the reliability of the grid was threatened.

The Fore Street Garage in Portland is the first such solar canopy in Maine, and produces a quarter of a neighboring hotels electricity.

Now, the world of strategic electrification has opened an unlimited number of possibilities for demand response – the internet has rendered it no harder to turn off 1,000 water heaters than it is to turn off a paper mill. Furthermore, a smart heat pump water heater will run when there is excess solar on the grid, but not when demand is high – basically performing the same function as a battery, but at maybe 2% of the cost, since all we buy is a switch telling it to run or not.

Our devices are increasingly able to communicate across the grid and operate only when most efficient. The “flexi-watts” they run on when there’s a surplus of renewable power will enable us to keep making the grid smarter. The grid is evolving beyond supplying electricity, into a network that makes the most of its distributed energy resources.

Much like the internet changed the way we participate with our media, it’s now changing the way we interact with our budding smart grid.

A Virtuous Cycle

Traditional energy efficiency metrics, that have been improving our electronics for years now, overlook the wide range of emissions efficiencies from electricity generation. Kilowatt-hours from different sources can have vastly different emissions profiles, ranging from as much as 2 lbs. of CO2 to almost nothing.

We need to improve emissions efficiency along with energy efficiency in our shift to an environmentally beneficial grid, by expanding renewable energy.

The worthy effort to reduce usage of dirty electricity through energy efficiency programs has been the focus of our policy and incentives, but when we consider the improved emissions of renewable energy, we see that it’s better to increase the amount of electricity we use when it comes from a clean source.

Pairing strategic electrification with a cleaner, smarter grid creates a beneficial exchange that inspires more electrification and greener electricity in a virtuous cycle.

On the Verge

We stand on the verge of massive opportunities through strategic electrification, but we must recognize that those opportunities won’t be achieved through an indiscriminate focus on reducing kilowatt-hours. It’s more important we clean up our kilowatt-hours, and use them.

If regulators and legislators fail to recognize the strengths of renewables and strategic electrification in a timely manner, there could be long-term negative impacts for us and the environment. Instead they can foster long-term growth, unlocking significant economic and societal benefits by getting to work on incentives and initiatives.

The sooner this is acted upon the sooner we can see all the ways a smarter, more flexible grid can increase reliability, security, sustainability, and open new opportunities for services and business. Coal was just the beginning of our electricity – and the Stone Age didn’t end because we ran out of stones.

This home in Maine has solar panels paired with a Pika Islanding Inverter and Harbor smart battery and can power critical loads during grid outage.

Big K.R.I.T. - "Keep The Devil Off (Take 1)"

Ariel Pink's Haunted Graffiti- "Bright Lit Blue Skies"

Notes on "The Impassive Hermit" and VICE

At the foot of the Southern Patagonian ice field in Chile (the second largest such ice field in the world outside of a polar region), and on a remote peninsula of Lago O'Higgins, a man named Faustino Barrientos has carved a stoic, almost entirely solitary existence since 1965. I do not know if he is alive today.

Faustino sipping yerba mate in his home made from an upturned boat.

Faustino Watched the Mountains Rise

When the world at large last heard from him in 2011, he was 81 and still living the as a gaucho. Another gaucho, George Lancaster, who was living nearby, would inherit his land. Even with the presence of this relatively new companion, it would be splitting hairs to argue over referring to Faustino as a proper hermit. Since 1965 he lived alone, and only traveled to the nearest town every few years to sell cattle, before retreating once more.

In the long history of people "leaving the world," the motivations generally boil down to either seeking a spiritual state of being, or avoiding other humans. The spiritual type, from Siddhartha Gautama to Thomas Merton, in general, paradoxically feel that leaving the world brings them closer to to it.

Those that leave the world because they are uncomfortable with society have a variety of perspectives. From a cabin in Montana, Ted Kaczynski lashed out with bombs sent through the mail at what he saw as a world led astray by technology. Christopher Knight, the North Pond Hermit, who simply felt he didn't fit into society, haunted a relatively populated lake area in central Maine for decades, pilfering food items and belongings from the hundreds of surrounding homes and cabins.

Whoever they are, and whatever their motives, it seems clear that they all just want to be left alone - yet we insist on looking in. To many of us who cherish companionship of loved ones, the thought of someone who would prefer unending solitude is too strange to ignore. Even Heimo Korth, who started a family in the far reaches of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge of Alaska, said, "The stomach needs food, the mind needs people."

The Impassive Hermit

A reporter, Roberto Farías, talked to Faustino in 2oo8 and wrote "The Impassive Hermit," a compelling article that explored Faustino's contemplative nature, and inscrutable exterior. VICE caught on to this story and sent a film crew for their program Far Out in 2011. They did a decent job of documenting Faustino's life at 81. It's truly impressive to see the man wielding a chainsaw, or jumping up onto a horse, but they did not delve into his contemplative ways. VICE was successful at bringing him plenty of media attention, how much of it ever reached his shores I don't know.

I believe the more compelling study of Faustino is the original by Farías, which I've had to roughly translate from Spanish. Even with my incomplete understanding, I find it far more helpful to understanding Faustino, though VICE's video serves as a beautiful illustration.

Since 1965, Faustino Barrientos has lived alone on the shores of Lago O'Higgins in a house built from the remains of a fishing vessel. He's a pastoralist, living mostly off the land and his livestock, with few modern amenities. His nearest neighbors are in Villa O'Higgins, a small community of several hundred people, 25 miles away, accessible only by a two-day horseback ride through rugged mountain animal paths.

Every few years, Faustino makes this ride to sell his cattle in town. At 81 years old, Faustino's self-imposed isolation was being increasingly encroached upon by the forces of government, economy, and tourism. However, Lago O'Higgins is one of the most remote areas of Patagonia and is the least populated region in Chile. It is also one of the world's most sparsely populated places outside Antarctica.

Faustino's land has two buildings - a small hut where he sleeps, eats, listens to the radio and pours over stacks of newspapers when they are delivered to him twice a year. The other building stores boxes of food - tins of soups and desserts, bags of sugar and flour, tubs of lard - which are delivered by a boat that has started passing his quiet corner every ten days.

Glaciers Retreat, Mountains Rise

Excerpted from a follow-up article written by Roberto Farías, the observant Faustino witnessed isostasy, a fluctuating geologic equilibrium between topography and the weight of ice upon the earth's surface, in this case:

The first time I was with Faustino, in January 2008, among many silences and monosyllables, he showed me a rock on the beach in front of his house where he sat down to watch the sunrise on the same day in October for many years, and he released the first of many deep thoughts:

"The shadow of the mountain range has run from here to there," he said. The shadow of a peak range that the October sun projected to reach the rock, had run, oddly, a few centimeters in those years. He had not told anyone, but from the shadows, had deduced something alarming or the mountains was rising or soil beneath our feet was sinking. Maybe mention it again all day, but the puzzle was more than enough for me. We talked about a few other things, showed me around his daily life, I left and began the long walk back. Then I checked with scientists that their observations were correct: the mountains were rising.

Here's the original conversation about the mountain's shadow and the full original article here: The Impassive Hermit

On the frigid, barren shore of Lake O'Higgins, at the foot of the homonymous glacier, at the end of the Aisen region, in a great nothingness, the hermit Faustino Barrientos lives in a house made from the remains of a boat's cabin. With Tibetan patience, for more than 15 years he sits on the same day of October on the same stone to see how the dawn casts the shadow of a mountain peak on a rock of the ground.

"In the last ten years the shadow of that peak that is there-points to a very noticeable curved tusk, 10 km on the other side of the lake, has run from here to here-accurate.

In principle, look at the small and supposed displacement of the shadow, does not produce anything. It is a subtle 2 cm increase.

"Tell me if I am correct - continues. Is the mountain range rising or is the ground sinking?"

"It is a riddle?"

"No, then. It is true. I'm asking you"

The wind that comes down from the Southern Ice Fields curtains the skin. The calypso water of the lake is half Chilean and half Argentine. Waves splash icy drops that burn the face. In winter, small icebergs pass by the wind. On the shore there is no grass, just some stoic bushes and charred trees. Difficult to take the question seriously.

The overwhelming intrigue is deep and enigmatic for Faustino Barrientos. He is 77 years old and has spent the last 51 living alone in the middle of Patagonia avoiding contact with people. He is, strictly speaking, a hermit.

Again, the above quote is from the original article which can be found through this link.

Below, is a follow-up article by Roberto Farías, shared in full. I have only been able to locate it on a random Facebook page, in a very unrefined state. I have no idea where this was originally published, but I do believe it to be written by Roberto Farías after Vice's Far Out documentary. I have attempted to edit for clarity, as the original was likely pushed through Google Translate:

APOLOGIES FOR A HERMIT Four years ago the journalist Roberto Farías published The Impassive Hermit for Paula magazine, the story of a lone inhabitant of Patagonia, who had detected subtle signs of climate change. The article was replicated many times and even a television station in New York made a documentary about the character. Now, Farías tells how to emerge from anonymity, the hermit was harassed, threatened and even invaded. This report is a mea culpa and a reflection on how journalism, when reporting a story, you can dramatically interfere in the lives of its protagonists.

Bernardo, Adriana, Peter and John: a director, a journalist, a photographer and a producer from New York come to Patagonia to do a documentary for the Far Out program, agency and editorial vice on Faustino Barrientos, a kind of hermit on which I wrote four years ago and that Paula had 51 living alone in O'Higgins Lake at the foot of the Southern Ice Fields in southernmost region of Aysen. I, on principle, I'm just going to visit Faustino Barrientos and accompany to guide them on their land.

The article that I wrote about him four years ago, entitled The Impassive Hermit, took flight itself. It was replicated on many websites and even an artist made drawings with Faustino's impassive face with their lenses as the last century. Other students wanted to make a visual for his thesis. And from New York wanted to make this documentary.

Finally, last December, we went to record it for a week. VICE had recently been in Alaska with a bear hunter Heimo and his Arctic refuge. For the next chapter the choices were between Faustino and a horse breeder in Siberia. The mini documentary came out this March in 30 languages, in the Far Out program, which was reissued in cable television and internet. It is directed by Bernardo Loyola, a neoyorquinomexicano (New Yorker/Mexican) filmmaker, who has worked with Michael Moore. It's called: The Withdrawal of Faustino in Patagonia, and can be seen on youtube (you can watch it below this article).

Since my trip four years ago, I had not returned to the land, until now, accompanying the documentary. As we went deeper into Patagonia, from Coyhaique, Cochrane, Villa O'Higgins, the difference with my companions Americans became increasingly marked. For them everything was new and surprising. Each waterfall or river jumped from the truck as astronauts reach Mars. For me, however, soon took a turn that had not foreseen: I began to notice the dramatic changes that my article had caused in the life of Faustino. Much more dramatic than the melting-threatening environment.

NEW GOGGLES

The first time I was with Faustino, in January 2008, among many silences and monosyllables, he showed me a rock on the beach in front of his house where he sat down to watch the sunrise on the same day in October for many years, and he released the first of many deep thoughts:

"The shadow of the mountain range has run from here to there," he said. The shadow of a peak range that the October sun projected to reach the rock, had run, oddly, a few centimeters in those years. He had not told anyone, but from the shadows, had deduced something alarming or the mountains was rising or soil beneath our feet was sinking. Maybe mention it again all day, but the puzzle was more than enough for me. We talked about a few other things, showed me around his daily life, I left and began the long walk back. Then I checked with scientists that their observations were correct: the mountains were rising. I spoke about in the article I wrote.

I remember on that first visit, the wind from blowing the Southern Ice Fields ruthless on the shores of Lake O'Higgins. Sometimes reached 90 km per hour and the faint sparks of water given off by the waves turned into hurtful ice projectiles reach the shore. To get around it, Faustino had done with his own hands a beautiful goggles browser horsehide and glass lanterns he saw in a magazine. As a geographer who visited him after his appearance in Paula gave him better, high mountain goggles, on this second trip gave me the old ones. Before I had given some maps of 1900.

REACH THE INVADERS

When I wrote that story did not know what this intelligent man separated from the rest of the world was a subtle balance that would break like a wall of sand.

The text of the report came over the Internet to Villa O'Higgins, the last village of the southern highway and the nearest land-Faustino but the authorities did not seem so good. At six months, police ordered to search his house for guns and the rifle that I had said that he had in his possession. The court cited the Cochrane 400 km north. He did not answer the first call and the second time he was picked up. First taken to Cochrane and then Coihaique. He had 60 years without stepping on the regional capital, and now was again as a defendant.

The world had changed. Vehicles, streets, buildings, light at night seemed day. He did not know how far it was from home, because he still uses as leagues. All were surprised, but still recognized him. "In a store," he recalls, "I was approached by a girl and she said, 'Are you the man from the depths of Patagonia, which appeared in a magazine?' And I said, 'Yes, that's me.' And she hugged me for a long time, as if hugging a tree." He paid a fine, bought clothes, the first mattress of his life and returned to his camp. But, as he had no weapons, animals were at the mercy of thieves and cattle rustlers, and himself, was at the mercy of Twisty Tiznado, his nephew and archenemy with whom, years before, had come close to death in the mountains over a land dispute and cattle. Thirty horses bred in the mountains, only one was left. Of 300 wild cows, only about sixty. He was losing everything.

The simple article suddenly pulled him from obscurity 51 years and shattered their silence and their property. "Until I was afraid they would kill me," he said. "Here nobody knows anything. Would have died without more." And thanks to the report, the government, so jealous of her solitary life, began to reach out: sending food, he donating an installation of hoses for water, installing VHF radio wave that does he not use, and he even had the mayor of Aysen to take a picture with him and give him a pension of grace under President Bachelet.

Then, with Piñera, solar panels led him to give birth to her home, but also because it interferes uses shortwave radio is their only contact with the world. Now, I resigned, stoic he accepts all visits. Years before, he would loose the dogs. And as word spread through Patagonia that he had no heirs, remote relatives came from all over to collect his inheritance in advance. They whet the appetite of uncles, nephews and grandchildren by inheritance or sell their lands in life. Appeared a brother who was living in Argentina, and then came back threatening Tiznado Twisty, his nephew, supposedly claiming unowned land.

Faustino finally realized that all was worth more dead than alive. He was afraid. For me, the article had been a source of satisfaction. For Faustino, it had just brought a ton of problems.

THE LAST RIDE

From our first meeting, Faustino has aged. Is now 81 and realize that this time might be his last ride into the mountains where once raising his wild cows. Giving away several rivers, cliffs, forests burned, beaches and lakes to reach the foot of the Ice Fields, which has a seat canoe (a kind of tiles made of hollowed logs), which remained the summer months gathering cattle for undertaken every two or three years the long trip to Villa O'Higgins to sell to traders of meat. Since 2007 not up to the mountains and just did. Basically, it was a farewell.

We arrived in front of Cerro Santiago where the mountainous horn cast its shadow on the stone. They remember it. But Faustino seems indifferent. No longer can go to the beach because your knees hurt a lot, watch the sunrise from her house through a window. He heard, like all Chileans, who in the 2010 earthquake the Earth's axis shifted a few degrees. "I want to develop a facility with a Goldy in the window you could see if it moved the Earth's axis as they say." No one knows, but that thing called gnomon (fin of a sundial) was invented by the Greeks to make the first astronomical observations. After the earthquake did the installation, tightened the Goldy and the floor of his home made a hole to drive the reference point. And set out to observe the October 20, which is the peak that reaches the sun on Cerro Santiago. But the 2010 and 2011 dawned cloudy and has not seen shit.

Difficult to understand the philosophy of life Faustino. It is not just for entertainment, but the basic cordura más allá por mantenerla (something like "to stay sane") survive. I'm not sure I've grasped the director of Far Out, who shows Faustino killing a sheep, sawing a log, crossing rivers on horseback, but nothing more nor nothing less!

THE PHILOSOPHER

In my version, Faustino Barrientos remains a contemplative. You just have to stop and listen. Leaning on the mount overlooking the horizon like those jeans Bonanza, I suddenly said: "Sometimes I think we're alone in the universe. That there is more to life than us." Nor is there much life at the end of Patagonia where he lives Faustino, almost no human being and it seems that nature had not yet finished form. So its strange conclusion is not surprising at all.

"It amazes me that so many lives on Earth," he continues. "Not only a few animals, but many plants, bugs, fish, bacteria, insects. Life on earth made every attempt to stay afloat you know? He tried all forms and single man could take off from the others. Why is that? "I abyss inexhaustible curiosity. Depth. As frequently heard Faustino science programs for BBC radio, France and Beijing International usually know more than you'd think. In a confusing mess, funny and even magic of atoms, molecules, cloning, fertilization, black holes and particle accelerator, concluded: "I think the man with his intelligence, will be able to create life. It will be his own God."

"Sure do many monsters before we create a similar nature to Patagonia. In their land there are twelve streams. Among the stream does not freeze and dirty stream, there are 1,720 acres of mountains and as many streams as yet unnamed. "This only God could do it," says Faustino. "I do not know why God. But God did." It is the nearness of death that leads to these depths of thought. "I know I will die sooner or later," he says preparing breakfast in the mountains. "But I'd rather die here on this earth before anywhere. So I prefer to give to poor man Villa (O'Higgins) before selling it to a millionaire.

Mea culpa

Andronico Luksic has been buying since the beginning of this century thousands of acres each year about Villa O'Higgins, near the lands of Faustino. As the only buyer, everyone wants to sell land, which has sparked a furor unusual trading in the small town. Many relatives or pseudo-relatives of Faustino also pressured into selling their land (valued at approximately 200 million). He had no choice but to give in his own way. Made an agreement with George Lancaster, a settler who sold their land on Lake Alegre Luksic to go to live with him in exchange for aid and protection. So at the end of this chain of changes in your life, now has a neighbor Faustino. Thanks to the media, the hermit ceased.

I apologized for all the trouble I caused. He remained with it a herd of wild horses on the shore of Lago O'Higgins: "It's fate," he said. "What can we do! But now I'll be famous, I will see in theaters around the world," naively ended referring to the program recorded. Now we just need that after seeing the beautiful landscapes on television comes the insufferable "entrepreneur" and after him the obnoxious tourists. My only consolation is that Faustino at this point will be dead.

"While there is a frontier, there's a place for misfits and adventurers," said Thomas Jefferson. Faustino is a mixture of both. I, however, I'm just a journalist who messes up from time to time. My horse, perhaps in retaliation, shot me twice. I know what you meant. Three condors hovering in circles in the sky because down in the cliff, there is a dead cow.

The VICE Far Out: Faustino's Patagonian Retreat Documentary

The Withdrawal of Faustino in Patagonia

!!! - "Hello? Is This Thing On?"

Exploring the Barrios of Palermo, Villa Crespo, Recoleta and Chacarita

In 2017 I had the chance of a lifetime to explore the neighborhoods or barrios of Buenos Aires for 3 months, while living in Palermo and Villa Crespo. The freedom to go out everyday and practice with my Fujifilm X-T10 helped grow my confidence in composing shots on the fly. Here I'll share my lengthy experience exploring the neighborhoods of Buenos Aires and practicing street photography for the first time.

Is This Real Life?

It had been a long time in the making for Zoë, but we had only recently met, and fallen in love, when she learned she had received a Rotary International scholarship. I remember her nerves when she first brought it up, before it had been granted.

She didn't know how it would go for us, given that it would send her to South America for 3 months, twice. I assured her I would be joining her. I am lucky to work for ReVision Energy, an employee-owned, B Corp solar energy company in New England, and they are supportive of their employees leading full lives. They approved my leave of absence and the game was on.

We left icy Maine in late January, dropping into steamy summer in the city of Buenos Aires (Bs As, as the cool kids say). We had a week to explore before I started Spanish language studies with Academia Buenos Aires - mostly we figured out where to withdraw money, where to find groceries, and how to navigate the subway, but we also had plenty of time to run through huge neighboring parks and swim in our building's pool. The 3 months ahead of us felt endless.

Though a partly cloudy day here, this became my Maine babe's tannest February yet.

Turn Me Loose

I was soon roaming block after block of Palermo (where Borges lived and wrote), experimenting with street photography. Language schooling went for three weeks, and was rigorous, but afterward I was completely untethered from having to show up anywhere. I realize how rare a thing that is.

I have been pushing myself to get better at photography for a few years now, developing my eye and technique, but time to really immerse into a practice is usually scarce. Here was a chance to shoot until I was exhausted, to dig into a new culture and explore one of the famous cities of the world. I had been dreaming about this prospect for months.

Everyone should exercise their own degree of caution, but I will first say that I never felt unsafe while walking Buenos Aires with my camera, often off the beaten path. The core barrios are a little rough in areas, but I never sensed the type of desperation that could lead to a mugging. Just check your surroundings and be conscious of other people, but not to a paranoid extent. Never, however, leave your camera unguarded at a cafe, for instance, because I have no doubt that non-violent crimes of opportunity could happen in nice places - especially Palermo Soho, where wealth is on parade.

Also in my favor: the mirrorless Fujifilm X-T10 I carried is small and reminiscent of film SLRs from decades ago, and so on that level I felt comforted that my gear did not shout, "DIGITAL! EXPENSIVE!" As well, at 6'2" I am not a small man, either, so I'm aware that I also experience a certain privilege of physical wherewithal. Nonetheless, I had 3-4 different people across the city tap my elbow to express concern for my camera. I thanked them and assured them I would be careful, but privately it never matched up with my intuitive sense of safety. Like I said, the core neighborhoods are not desperate places, especially during daylight hours, and even big city Argentines are often remarkably genteel people.

I did not explore La Boca. It has huge appeal, and you may be very interested in seeing it, so just know that it is widely advised to stick to the beaten path there. Probably wise to join a tour group, even.

Casual breakfast views of Palermo, Villa Crespo, and on the fringe, Chacarita.

Battery Steele is a decommissioned WWII bunker on Peaks Island. I took this with an iPhone 4 while working a carpentry job out there my first summer in Maine. I was beginning to look for photographs everywhere I went.

A Little Background

Northern New England and its difficult moods have contributed a lot to my interest in photography. After a substantial stint in Vermont, there was Downeast Maine over the fall and winter of 2013, where, from the deck of a Dutch mussel boat in the Mt. Desert Narrows, I captured brilliant skies, and scenes of austerity and silence that felt otherworldly to me.

In 2014 I moved down the coast to Portland, a fortified harbor town that still has the hardscrabble community and salty, weathered aura of an early colonial city, I imagine. I kept seeking scenes possessing what I could only describe as "magical realism," having some hint of energy from elsewhere.

Don't Sweat the Technique

Plaza Armenia rap battle, Palermo, 2017.

Hunkering down and photographing New England in this way without any major trips elsewhere for a couple of years made me feel like I had a particular style that would carry over wherever I went. It turns out that shooting in new places requires me to redefine my awareness and style, and that's alright because I'm finding that the observation involved is something I'm pretty good at.

In Argentina, I had nearly 100 days to explore, immerse, and absorb. Cumulatively this was as much time as I'd ever shot anything anywhere, and it wasn't long before a new style started coming through. But it wasn't until I went inside Cementerio de la Chacarita, or Chacarita Cemetery, during the second half of our trip, that I realized what was missing from my work: a project... but hold that thought!

I roamed the neighborhoods for a month or so before I found Chacarita Cemetery - I was always searching for old facades, tree-lined streets, funky cars and stylish Argentines to photograph. There's no shortage, and I feel confident saying Buenos Aires must be one of the coolest cities to practice in. There's such a juxtaposition of style and decay, Old world and New.

If I could have more time to photograph Buenos Aires' streets again, I would push myself to seek more photos of Porteñas, the women of Buenos Aires. I can remember sweet pairs of elderly mothers and grown daughters walking arm in arm, or young women enamored with enormous, studded platform sandals that boosted their height, and I wish I had a photo that captured it.

I suppose it was shyness, in part, that kept me from aiming my camera at the women of Buenos Aires, and in a way I was overly sensitive to the idea of how some women might be uncomfortable with a stranger snapping shots of them. There's nothing wrong with respect, but I need to get past my shyness, or the thought that people are largely against having their photo taken.

There was one occasion when Zoë was with me that we asked a pair of nuns for their portrait. They reluctantly obliged, and smiled, and then requested that the photo never be published! It is too good to not share it, someday, perhaps.

I'm practicing approaching people for portraits a lot more nowadays, and often they're happy to oblige, and are maybe even flattered. If they don't want to, they just say, "No," and life goes on! After the portrait, I feel like I should offer a copy to the individual, to make it worth their while, but I usually don't act on that feeling. How do the other photographers reading this approach that situation?

The Gates of Chacarita

All of that exploring led to my first significant project as an emerging professional photographer. We had seen an immense cemetery on the map, close to our upcoming neighborhood, Villa Crespo, and thought about doing long runs around it, since we were leaving Palermo and the traffic-free parks nearby.

Chacarita Cemetery's corner gate, 2017.

I love graveyards (cemeteries, dolmens, sarcophagi, etc.) so one evening just before we moved apartments, I went far out to go have a look at the cemetery. After a lengthy walk past boutiques and kioskos, across train tracks and thoroughfares, I approached a quiet corner of a massive wall as the sun moved behind it. "CEMENTERIO DEL OESTE" is engraved above a large gate, and through it I saw golden streets of mausoleums.

Still In Awe

I was fairly stupefied by the size of the wall. I followed a silent, tree-lined span of it to eventually find a central front gate. The hours were 7 am - 5 pm. I couldn't wait to tell Zoë. I had a feeling this was where I needed to look, but I still didn't have any idea what really waited in there.

I'll tell that story, soon, but suffice it to say, this was my first project, and the first time it felt necessary to put words with my work.

I've yet to write an artist's statement but I'm beginning to see how helpful in can be in attracting an audience. Lately I'm noticing that having a better idea about what I like to shoot has made me better at describing what I'm looking for. I feel that as I get better at creating images, and honing my expression, the seemingly distant notions of having my work valued as art or being sought for hire will begin to happen naturally in recognition. So, make work, share ideas, and maybe someone will dig it.

What say ye?

Read more about the truly amazing Chacarita Cemetery

King Krule - "Dum Surfer"

Stereolab - "French Disko"

Roosevelt - "Montreal" (Official Video)

Driving to see my grandparents in the mountains of Yancey County, my mama could see her window-gazing baby boy thinking too hard. “What’s wrong, Will?”

“I don’t know whether to believe in god or the big bang.”

“Well, honey, I think you can believe in both.”

The wheel of the world just turns.

At the end of my youth when I moved to Maine to work on that boat, I stopped looking through the glass and tried to get to the marrow. I’d taken that ride to get booked for some dumb shit. I’d spent everything I’d ever made. I’d hurt this good body.

The Dutchman had me watching the haul going up the conveyor into the heart of his floating factory that sorted rocks from starfish from muck from tin cans from sticks until there were only shiny, bearded bivalves rattling across the sizing grate and dropping through when they were above their bin.

He saw I liked the rocks that were shaped like hearts and told me, “Don’t give one to a girl, it will turn her heart to stone.” He was wrong about this and lots of things, but he was a good captain in the circle he sailed, at least.

I dreaded the minutes at my post, waiting for the machine to jam, slugging weak, scalding coffee, and torching tobacco in defiance of my grimly uncreative day. I ate peanut butter sandwiches from dirty hands and I was tough and I was gentle and I tried to relish it.

But there were stars and memories, and even as I slid into poverty despite caring for the very first time where my money went, every time the sun set I knew I was close to Xanadu.

Pain is not a punishment, pleasure is not a reward.

The delicacy of today was taboo just the day before. The bottom feeder bug is the taste they’d like to remember, trash food for the liberated soul.

This is the prisoner’s last meal meal in samsara.

From Feudal Isolationism to Global Excellence

I stumbled upon these old colorized stereographs showing facets of mid-nineteenth century Japanese life. For those of us who aren't easily prone to motion sickness, a GIF rendering of a stereograph is an exciting way to experience an image so that it nearly seems like the three-dimensional sight we receive through our binocular vision -- it is especially so for me when the image reveals another realm or cultural era.

Stereography was brought into public use by Sir David Brewster of Scotland in 1851, as the lenticular stereoscope. Simply put, two photographs are made a small distance apart, and when viewed simultaneously will create a left and right eye effect. Brewster was an accomplished intellect who experimented with optics in a myriad of ways, also giving us the kaleidoscope. (Curiously, despite his scientific proclivities he was among the first to speak against the theory of evolution.)

Europe and America could not get enough of his novel invention and over the years millions of stereographs were produced with the latest photographic processes and equipment, beginning with the daguerreotype print. Even Queen Victoria couldn't hide her excitement upon stereography's mainstream debut at the Great Exhibition of 1851. (This first world's fair was held in London and housed in the incredible Crystal Palace, something akin to the world's largest greenhouse.)

The lenticular stereoscope followed Commodore Matthew Perry of the United States Navy after he strong-armed feudal, isolationist Japan into opening their ports for trade in 1854. These colorized stereographs were thus created in this period when the Victorian world was freshly enamored with this visual experience, and when they were first becoming aware of a culture that had long been preserved from global influences.

The newfound might of the American navy exposed the weaknesses of the long-running Tokugawa shogunate, which was still holding power with its traditional tools of war. For better or worse, it was not long after these images were made that Japan began transforming into the modern imperial power that the United States Navy met again in the Second World War.

Today Japan is one of the most technologically sophisticated nations in the world, with a long history of excellence in precision optics engineering. They are also home to a few mobile phone manufacturers that are among the elite developers that continue to propel smartphone technology forward, and imaging capabilities are part of this evolution.

Stereoscopic technology has continued into the Internet era, being utilized by phone manufacturers as early as 2002. With the arrival of ever more powerful processors, Samsung, LG, and HTC have all produced 3D-enabling smartphones.

There is not yet a large demand for these devices, and it remains to be seen if excitement for stereoscopic imagery in some form can be renewed. In its time it was the most remarkable way to convey an image, but everyday smartphones can now record in time-lapse or slow-motion, instantly deposit images into a virtual cloud, and can even generate augmented reality (I'm looking at you, Pokémon GO). With so many citizens of the world holding a powerful camera in the palm of their hand, there will be no paucity of images for future armchair anthropologists like myself to peruse. I hope to give them something worth looking at.