Chacarita Cemetery of Buenos Aires

A History of Argentina's Magnificent, Broken-down Necropolis

In Buenos Aires there is an immense oasis sprawling over gentle slopes, and beneath the earth: a cemetery in the quiet neighborhood of Chacarita, nestled next to barrios Colegiales, Palermo and Villa Crespo. Graveyards are one of my favorite places to explore and photograph – they often have lovely old trees – this one, Chacarita Cemetery, has an origin more grim than ordinary, and is one of the most fascinating places I have ever been.

Spread over 95-hectares, Cementerio de la Chacarita is almost twenty times bigger than Cementerio de la Recoleta, the famed resting place of Eva Perón and many other wealthy families. Almost half of barrio Chacarita's territory is occupied by it.

17th century Jesuits lived on the land where barrio Chacarita is today, but they were expelled in 1767 by the Spanish Royal Crown. The name Chacarita comes from the Spanish word chacra for small farms like the ones belonging to the Jesuits.

It was clear once we looked at a map that Chacarita's cemetery is massive. It is not just a dominating landmark of the barrio, but also a significant feature of the city. There are other extensive green spaces, like Los Bosques de Palermo, and numerous other parks spread throughout the city for the enjoyment of some 3 million residents, but this cemetery is a distinctly quiet place.

I didn’t really grasp the magnitude until putting eyes on it after trekking across Palermo before an upcoming move brought us to the adjacent neighborhood. Zoë and I were living in Palermo, the hippest hood in town, on Guatemala y Armenia (not far from Tufic). We had thoroughly enjoyed that arrangement, but were moving one neighborhood away to Villa Crespo to seek a different experience, and perhaps more peace.

With what must be 30 foot high walls around much of the property, Cementerio de la Chacarita is like a fortress. I wrote about this first encounter briefly in an earlier essay, and the stupefied feeling the sunset introduction gave me when I glimpsed golden streets of mausoleums through a gateway.

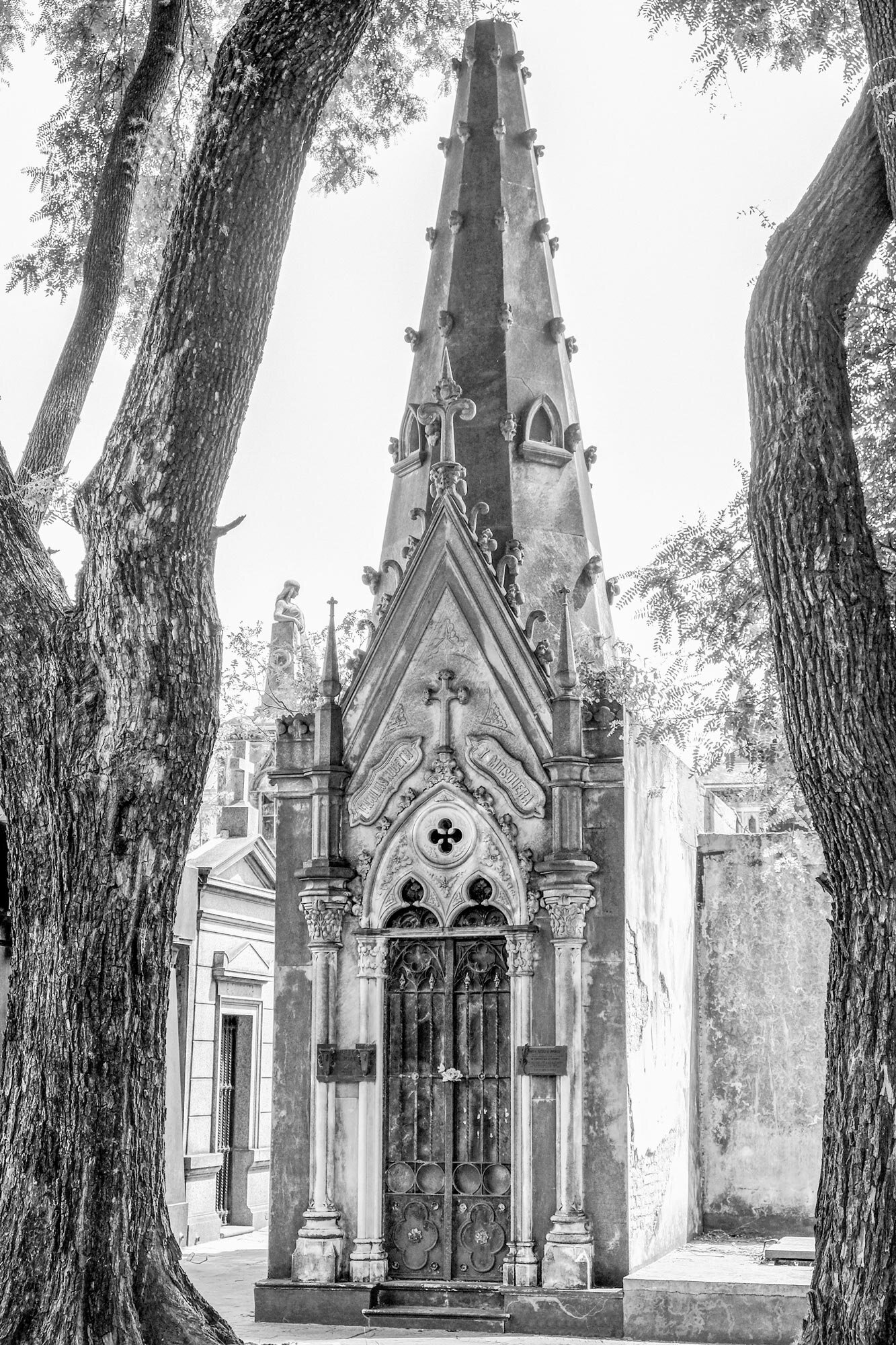

I returned to explore within shortly after we moved apartments. I strolled up and down the somber streets of tombs, and quickly observed that some were cared for and others were falling apart. One mausoleum's marble surfaces would be so pristine that I could see my reflection, whereas the one next door may have broken panes of glass and trash accumulating inside.

I wove through, trying not to miss any details, and eventually emerged at a new segment of the cemetery. It didn't look like much: an expanse of grass with several large concrete awnings spread across. It was also a hot day, and I wasn't overly interested in spending much time in the sun without water, but I went out to get a closer look.

I remember approaching a railing and looking over, down into the earth, and seeing a verdant courtyard several levels below ground. It was surrounded by layers of catacombs. I realized, then, that those great awnings were entryways down into the underground galleries of Argentina's past lives.

I returned again and again to wander the catacombs. I love the vibrancy of Buenos Aires, but silence is what truly nourishes me, and down there I found a new experience with silence that was enhanced all the more by the scenes I saw. I spent hours underground trying to be lost, trying to find every last corner and seek photographs that could describe the feeling. I was struck by the contrasts – shades of lost civilizations and brute futurism, vastness and intimacy.

Outbreak

1871 was a devastating year for Buenos Aires and neighboring cities, and Cementerio de la Chacarita is intrinsically linked to it. An outbreak of yellow fever, the mosquito-borne virus, struck the barrios near the port, lowlands, and floodplain areas where mosquitoes could easily proliferate, and soon it was everywhere. Mosquitoes are difficult to avoid even when one is aware of the threat they can pose, but at the time it was not even understood that they were the carrier.

The Episode of the Yellow Fever, circa 1871, by Juan Manuel Blanes is a haunting rendition of the pain brought to Buenos Aires, but also a depiction of illness befalling a specific household. One wonders how many scenes like this the People's Commission had to see. José Roque Pérez is depicted in the center with with his hands clasped.

The epidemic wreaked havoc in the city, with hundreds of deaths every day during its height. Also known as "black vomit," the illness upended daily life as businesses closed, residents fled, and thieves ransacked.

The dead were so many that wagons couldn't transfer them quickly enough, furthermore, the existing cemetery space that would accept victims of the fever became full. Coffins soon accumulated at the gates as the disease spread by leaps and bounds.

The city needed to increase its burial grounds, and Chacarita was chosen as the location for a new cemetery. Cementerio de la Chacarita was inaugurated on April 14th, 1871. The first to be buried was a bricklayer named Manuel Rodriguez.

The Western Railway quickly extended a line that would transport the accumulating dead. The train that performed this twice-daily task was named La Porteña, but became known as the "train of death."

The People's Commission was soon formed to handle the ravages of the epidemic across the city. The leader, José Roque Pérez, a prestigious lawyer shown in the painting to the left, succumbed to yellow fever along with many others who did not flee.

Over 13,000 people of the city's some 180,000 residents died in just several months, before the cold arrived and killed off mosquitoes. Normal life resumed in time, but this quote from Guillermo Hudson's "Ralph Herne" indicates that the city was haunted by the catastrophe for years after:

"...But the years of peace and prosperity did not delete the memory of that terrible period when during three long months the shadow of the Angel of Death extended over the city of the nice name, when the daily harvest of victims were thrown together — old and young, rich and poor, virtuous and villains — to mix their bones in a communal grave, when each day the echo of footsteps interrupted the silence less often, when like the past the streets became desolate and grassy."

Cementerio de la Chacarita has since become a place of worship and remembrance. Everyone is welcome in Chacarita, from the less-fortunate to the famed. The soil there is for intellectuals, artists, boxers and ordinary people. Cementerio de la Recoleta, which turned away victims of the epidemic, has always been more aristocratic and exclusive.

While Chacarita receives more residents than Recoleta, it has far fewer visitors. During my time there I never saw any other rovers like myself, just visiting relatives, caretakers, and a funeral gathering. I found it comforting that it's still a very personal place for Argentines. I felt privileged to explore the grounds and tried to maintain a respectfully low profile.

It was inaugurated as the "Cemetery of the West" in 1886, but its popular name stuck, and it was officially renamed in 1949.

Over the years its mausoleums became equally as splendid as Recoleta's, with an abundance of styles and design. Its grandeur endures, but has become worn down in many places. Though some of its aging is serious, I never thought of it as anything but beautiful.

Recently the union workers formally expressed their concern about the aging. There is a degree of abandonment, and water damage, which has resulted in the crumbling of masonry and deterioration of ceilings.

The underground galleries are the most worrying in regard to potential structural issues. In many ways they are lovingly tended to, but there are damaged ceilings and broken floors all around. As well, many of the elevators are out of order, lights are missing, and there are pigeons nesting all over. Saplings have sprouted in odd places and some of the gardens are in need of pruning and attention.

I do not know when the catacombs were built, but based upon some of the building methods and mechanical features I would guess it was in the 1960s. Thinking back on how many nameplates I passed, I could've looked for dates to try to ascertain a general period of time, but the number was overwhelming.

Around the world there has been a shift, over the last few decades, toward cremation instead of burial. It seems this and the correlating decline of visitations have contributed to delinquency in payments for the niches of the galleries.

The declining number of burials and visitations signifies a cultural change in how people remember their loved ones. This could be confirmed by the florists that are found around the outside wall. Those who come to leave flowers in the tombs and in the niches are often elderly people who still retain the customs of other times.

If Cementerio de la Chacarita is to remain a safe and beautiful place, it may need monetary help in a big way before much longer. For now, in its massive underground breezeways there is a pull between the polished, sterile spaces that are both immaculate and neglected, and the lush groves that are at the same time cultivated and wild.

I'll conclude with with this description I wrote after my first day in the catacombs:

"Daylight filters in from the surface with the chatter of swirling green parrots, all else quiet. There is an allure to staying in the cool air of this geometric cavern, wandering what seems like an unknowable layout, but much of the sense of calm I feel may be reliant upon this subterranean library of the dead's frequent connection to the sky and wind."